Primeval forests first appeared on our planet in the Devonian Period, 380 million years ago. They were very tall, magnificent and abundant with animal and plant life.

Before the appearance of the human species 40,000 years ago, all of the Earth’s forests were primeval. Humans have been clearing, exploiting and deforesting them at an ever increasing rate.

A primeval forest is a forest that hasn’t been exploited or cut down by man. If it has been in the past, then a sufficient amount of time has elapsed for the forest to become primeval again.

In humid tropical or equatorial zones, where trees grow all year round, it takes seven centuries for a cleared area to be reclaimed by a primeval forest. In temperate zones, where trees only grow five or six months a year due to winter, it takes about ten centuries.

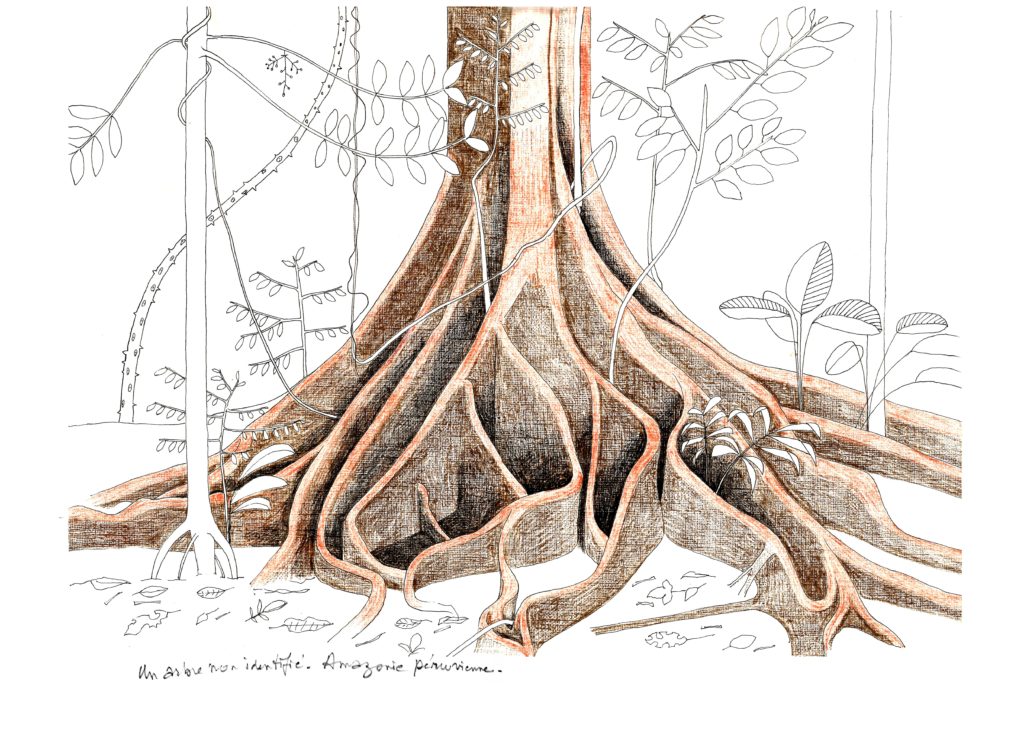

In a lowland tropical primeval forest, trees are tall (50-70 meters in height, or approximately 164-230 feet) and the undergrowth is dark because the canopy – the upper layer of trees – intercepts up to 98% of sunlight. (Light is abundant on the canopy, where 75% of the fauna is found. It is very humid because it rains during the day, and a blanket of mist covers the undergrowth at night – all year long.

The darkness of the undergrowth is sometimes cleared due to windthrow. This can affect close to a hectare (2.5 acres) of land when a large tree collapses and its vines drag the neighboring trees down with it. Windthrow is useful to the renewal of the primeval forest. By bringing light back to the undergrowth, windthrow allows pioneer trees to grow in turn and the forest begins a new cycle. The gigantic fallen trunks decompose over the course of a few months, sheltering a wide variety of fauna and nourishing the soil.

Forest wildlife is often hard to see in the daytime, but it is always noisy. It is most silent at the hottest hour of the day and loudest at night. It is also easier to observe wildlife in the undergrowth at night, as different zoological groups gather on the canopy, producing a nocturnal concert: aboreal amphibians, cicadas, nocturnal birds, hyraxes, etc. The birds’ songs get very loud just before dawn.

Lowland tropical rainforests represent the maximum of the the world’s biological complexity and diversity; almost all living groups are represented there. There is also a paradox with regard to trees: rare species are ubiquitous whereas common species are scarce. In equatorial forests, one often has to travel several kilometers to find two trees of the same species, and inventories of 100 different tree species per hectare are common. It is impossible for humans to /manage/ this kind of biodiversity, and to be effective we must adopt a collective approach.

The primeval forests of the equatorial plains are located in the Amazon, Indonesia, Melanesia and the Congo Basin. With 90% of its territory covered by primeval forests, French Guiana is home to one of the largest regions. Another paradox is that no matter where these forests are, they all look the same – the same massive tree trunks, the same light, the same sounds and the same smells – and yet, all of their plant and animal species are different from one continent to another.

Whether it be in Africa, America or Asia, the human populations of tropical primeval forests have never destroyed them or altered their primeval nature. Deforestation in these regions is akin to genocide, because without their forests these populations are deprived of their daily resources, shelter, culture and often times, their lives.

Temperate lowland primeval forests are found in British Columbia and along the western coast of the United States, Tasmania, New Zealand and the Southern Cone of South America. In Europe, very few lowland forests have been preserved from exploitation. Poland’s Białowieża Forest is the oldest, having formed 10,000 years ago during the last ice age. It is also is one of the last remaining primeval forests in Europe and a haven for some of the continent’s last bison still alive. It is extremely beautiful.

Once a tropical or temperate primeval (or primary) forest has been destroyed, a secondary forest develops, with very limited biodiversity at first that increases over time, provided no predationf/ occurs before it grows back into a primeval forest.

According to the UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), more than 80% of the world’s original forests have been cut down in the last century. Every year, 15 million hectares of primary tropical forest – the size of England – are deforested. Trees absorb carbon dioxide, release oxygen and purify the atmosphere. We wouldn’t be able to breathe without them because photosynthesis is our only source of oxygen. Without trees, the human species would be in grave danger.

Given these circumstances, the restoration of a primeval forest in a densely populated area like Western Europe could be a way of reconnecting with a sense of time and the long life-cycles of trees, while reconciling man with unspoiled nature.

Why a primeval forest?

Most of the large countries located in temperate latitudes – the United States, Canada, Chile, Russia, China, Japan, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand – have managed to conserve primeval lowland forests, whereas in Western Europe our ancestors destroyed them, unaware that they had irreplaceable ecological value; in Europe only one remains, that of Białowieża in Poland, which is, alas, under threat to its very existence, despite reminders to do so from the European Union.

The association was set up on the premise that it was unacceptable for Europe to be left with nothing but tree plantations and secondary, exploited, artificial forests with degraded biodiversity. Our aim is to create the conditions for a return to lowland primary forest in Western Europe, with the high biodiversity that was characteristic of our regions before they were deforested.

In the current context of dramatic degradation of the planet’s biodiversity and massive greenhouse gas emissions, such a project is, on its own scale, a major issue of general interest. Added to this is the exceptional scope it would open up for scientific research.

Where will this project be located?

t be located?

Two areas are currently being considered by the association for the development of the project: the Franco-Belgian Ardennes and the region combining the French Vosges du Nord and the German Rhineland-Palatinate.

These two areas meet three essential criteria:

- a cross-border character, as the project is fundamentally European in its scale, trans-generational character and scope;

- a strong forestry tradition and identity, with ancient massifs rooted in the culture of the local inhabitants, in low-lying areas where temperate hardwoods grow naturally, threatened everywhere by the replacement of species considered more « productive »;

- mostly public forests, as the project does not aim to purchase land, but to protect forests already in the public domain: it is already recognized as being in the public interest and is fully in line with this objective.

Our project is ambitious, both in terms of its surface area and its duration.

The surface area, 70,000 hectares, corresponds to that of the Polish part of Białowieża; it is necessary because of the presence of the great European forest fauna.

While it can take up to 10 centuries, it depends on the age of the original forest; that’s how long it takes for forests to reappear in regions with cold winters, where trees only grow for five to six months a year, and no one can shorten that time, or speed up the process. A return to a high level of biological diversity requires us to make use of the long time frame of nature and of the forest itself. The current pace of our lives is often frenetic, and we would do well to rediscover, through this forestry project, a sense of the long term and of transmission between human generations.

What happens when the required area is selected and marked out, and the experiment begins? First, we’ll see the natural death of the pioneer trees, pines and birches, whose dead wood will enrich the soil and encourage a diversity of fungi and insects. Then, without any planting, we’ll see the appearance of post-pioneer trees, ash, lime and maple, which will build up the forest before aging and disappearing in their turn; it’s then that larger animals, such as bears and bison, will be able to take advantage of the clearings and the first windfalls. Finally, oaks and beeches will take their place, and the primeval forest will continue to grow in height and enrich in plants and animals.

During this long period, when the forest will evolve freely and naturally, all harvesting and poaching will gradually cease, but Europe’s primeval forest must remain wide open to visitors. Reconciling these two divergent imperatives, without them becoming contradictory, requires the collaboration of diverse skills.

Our current aim is to ensure that our project is no longer just a national one, and that, for reasons of stability and security, it becomes a major European project, integrated as such on the specific issue of the need to revive large primeval forests, with existing schemes and measures or those being constructed by Europe, such as the Green Deal launched by Mrs Ursula von der Leyen.

Cover photo: In the heart of natural forests, every death gives way to a multitude of new lives. Trunks and branches are quickly colonised by a wide variety of plants, insects and fungi. Light floods back into the forest, providing opportunities for dormant seeds, while windfall provides food and shelter for young shoots. Jessica Buczek